I was born in a Catholic hospital in a small, semi-rural community in the mid-seventies. My mom checked herself in in the morning and didn't have me until nearly midnight. During that time, she apparently repeatedly refused meds of any kind - probably even saline, it sounds like - because she wanted to have a totally med-free birth. Before I was born, she had even insisted on having a hospital tour, at which point most people thought she was out of her mind, because you just didn't do that back then, apparently.

The response to no pain meds was this: My mother labored all day and most of the night, in a room by herself. Nursing staff probably saw her as a difficult patient because of her refusals, and decided to basically completely abandon her as a form of punishment.

Ina May Gaskin talks about this in her book, Ina May's Guide to Childbirth, when citing the story of a woman laboring in a New York City hospital in the late 1960s. With no hospital beds left, apparently, the woman was relegated to an empty gurney in the hallway, where she labored the entire time. Nurses, apparently, were the same brusque, seemingly uncaring kind that my mother ran into during her labor. I can't remember if it resulted in a c-section, but I wouldn't be surprised: lying flat on your back during labor works against the nature of gravity that can help the baby move down the birth canal, not to mention it is extremely uncomfortable, to say the least.

Another story, from around the same time period, involves a friend of mine (whom we'll call SB), who was ready to deliver her second child in the space of one year. You could say that, because her children were so close together, that perhaps her body was more primed to birth, and as SB arrived at the labor and delivery unit, her baby was nearly crowning. The nurses insisted on giving her an epidural, (insert "You're going to need this!" here), to which SB replied that she didn't want, or even need, one at that point. What good would that do? You're nearly done!

And lastly, the story of a friend's mother, who birthed her daughters throughout the early and late 1970s, who was given, against her knowledge or will, a pill to dry up her breast milk, even though she was adamant on nursing her newborn. In a panic, she asked her pediatrician if she'd still be able to nurse, and he assured her she would and that everything would be fine.

I find that even though many of these tales seem crazy, the same thing kind of still happens today. Perhaps procedures aren't as overtly clandestine, but patients seem little more informed than they were then. No wonder the pro natural birth movement was spawned in the 1970s, probably because of the nearly robotic nature obstetrics had taken on. In some of the mothering circles I've frequented, the overuse of Pitocin, epidurals and c/sections almost seem to harken back to those days, and for a minute you again start to feel like the anomaly - or at least like a troublemaker, for daring to speak up and question something that just doesn't sound quite right.

In "the old days," births were often attended by the mothers, sisters, aunts, and other female relatives of the laboring woman. Usually with nothing more than personal experience - whether it be from having gone through labor before or having attended hundreds of births - a midwife delivered the baby, and those deliveries were often deeply spiritual events that signaled a rite of passage. I can attest that there is nothing more spiritual or empowering than giving birth in the company of women, something I will never forget from my one vaginal birth. Not only did I physically give birth via VBAC, but to a daughter - under the direction of a midwife, with female nursing staff in attendance. While it was a hospital birth, I no doubt labored with women who were sisters, wives and mothers - all of whom have probably attended the births of their sisters, nieces, daughters ... there was something so beautiful about that that I just explain any other way.

While there were negative outcomes of childbirth before modern conveniences, technology and information, there were also many positive outcomes. And sometimes, unfortunately, there can still be negative outcomes even with a modern hospital birth. Some of these things, as Ina May hints at, can be prevented, but some cannot, and I think that's very difficult for some people to accept. With the onset of tons of medical interventions, you're often taking away the deeply feminine aspect of birth - as well as creating more problems in the long run. This kind of thinking has totally changed the way obstetricians practice medicine, as well as how the women in this country give birth, as evidenced by the c-section rate in the US that hovers around 33 percent.

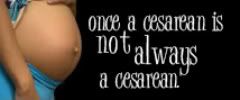

We seem to have traded one set of concerns for another: yes, the infant mortality rate has improved with modern care, but our cesarean section rate is definitely increasing. Back when doctors (and midwives!) knew how to turn babies in the womb, deliver breech-presenting babies and manage difficult labors, c-sections were rarely performed. It seems, however, that in many other countries - that also practice modern obstetrics - the rate of cesarean is much lower, no doubt because doctors respect and practice concurrently with midwives, and still practice many of the 'old school' techniques our doctors have long-abandoned.

Women who are informed about their care and act on that information are often discriminated against, treated rudely or seen as nuisances by their doctors. In talking to many of my friends, the routine model of OB care seems to be one of two paths: You approach your due date, possibly go overdue by a day or two, and the doctor brings up the possibility of induction. You decide to do it, and either the baby is born on the doctor's time table (between the hours of 9 a.m. and 3:30 p.m.) or the induction fails, and you are shipped off to the operating room for an "emergency c-section" for fetal distress. End of story.

In the meantime, it seems that that model of care mirrors the kind our mothers received - treated, on the whole, as robots, whose job is to just lie there and shut up, no questions asked.

0 comments:

Post a Comment