It's not much of a secret that American public schools are in the proverbial toilet. That's not to say that all districts are bad or fail their kids, but let's not kid ourselves: it seems that somewhere in the equation, we have screwed up. Badly.

My apologies to those who like this guy (I've never heard of him - does that make me uneducated?), but after seeing this meme on FaceBook I just kind of shook my head.

Hmm...did he really say this? Something didn't sound quite right here. His disclaimer: "Even though I don't personally have a kid in school" made me wonder if he was even old enough to have kids. Apparently he does, but I don't know if they're old enough to be in school yet. Even if they are, do you think with his wealth and fame he's going to put them in public school? And even if he is, again - with that wealth and fame he can pretty much move right in to one of the best, wealthiest districts in his area, I'm sure.

Because I didn't know who this person was, I looked him up. He was educated in a boarding/country day school and then moved on to the rural but prestigious Kenyon College, a private liberal arts college in Ohio (that is not that far from where I spent my formative years). I have lived as a faculty spouse in the boarding school culture for over a decade, and am quite familiar with its demographics: mostly made up of either parents who are scraping everything together to help their kids where the public school failed them, or parents who could literally write a check for the $50,000 tuition without batting an eyelash.

Either way, because we're a school that specializes in teaching kids with learning "differences," they're here because their former public school failed them. They're here because their public school either could not, or would not, give them what they needed to succeed.

As a product of the public school system myself, I caught on quickly to their schemes: tracking and grouping "smarter" students and sending them to the brighter, more engaged and dynamic teachers, while the rest of us were going in the other direction. I quickly noticed how the TAG (talented and gifted) program primarily consisted of the smartest kids in my class. I was there when, as we stood in the hallway looking at the class roster for the coming year, a fellow student who's mother was a substitute teacher was horrified to learn that she'd been placed in the teacher's room that ended up making my life a living hell for much of fourth grade. (It wasn't long before her mother protested and changed her to the other teacher's class, and I wondered to myself, What's wrong with this teacher? What does her mother know that mine doesn't? Why doesn't my mom move me, too?

As it turned out, that fourth grade teacher would chastise me for my problems in math, calling me to the board to be embarrassed in front of the entire class time and time again. Meanwhile, in my head I was silently criticizing her for her professed inability to say the word 'aluminum.' Years later my mom told me told that classmates of mine asked her, "Why is the teacher so mean to Carrie?" Therein began my absolute hatred for math.

Fast forward a couple grades - after we stopped being separated by "smart kids, dumb kids" - and I was distinctly told by at least one of my teachers, "Oh, I've heard about your struggles in math." I thought to myself, Yes, and what are you going to do about it? I was again horrified and embarrassed. My high school algebra teacher separated me from the class, making the rest wait in silence as he went over negative numbers and integers with me. At one point during that year, I left the room in tears.

It was only when my chemistry teacher took the time to teach me a different way, to help me outside of class and away from the stares of my peers, that I really got it - and actually started to enjoy math. Somehow I can function just fine in my world, despite not having taken higher-level math - a reality that became crystal clear to me as I took one standardized test after another to assess what I knew and what I should know. The math questions always stumped me and I basically just started guessing. It occurred to me: This is an assessment of what the state thinks I should know. But what if I don't? How can I answer questions on a test when I've never even seen this material before?

I think of the learning-disabled kids who went to my school - stuck in the resource room, which translated into "party time!" They were kids with behavioral problems and bad grades, and it's hard to tell which came first. It's obvious when reading their status updates on FaceBook that they still clearly struggle with reading and writing skills, and I feel badly for them. They were just shuffled around, probably never made to think they could succeed. What if they had untapped potential and could've been helped in a different way? Even though this was during the 80s and 90s, don't think it still doesn't happen in schools today, despite all the legislation, funding and government intervention that tries to tell us differently.

I took "advanced placement" English in high school, which was nothing more than a year-long session of glorified spelling tests. We read one book the entire time. I got mad about it, admittedly disrespectfully arguing with the teacher in front of the entire class about how when I got to college, my English professor was going to laugh in my face. I asked the school's librarian about it, and she knew full well the problem, puzzled because that teacher's house was "full of books."

We are fortunate to have the opportunity to send our children to a private parochial school that has the cheapest tuition I've ever seen. But we're hoping to move closer to family, which makes me wonder if we're not crazy for giving up such a good deal (too bad it's only K-8). When I compared private education costs elsewhere, I was literally blown away. One school charges $6,000 a year for full-day kindergarten alone. How can we possibly afford to educate three kids there? Couple that with housing costs, and just in order to find a house reasonably within our budget, we're looking at sketchy, poorly-rated districts, if not some of the worst in the area. What do really poor, low-income people do? Just give up?

I think back to my conversation with a private school administrator currently facing low enrollment (because no one wants to shell out the big bucks for private schools) and a number of questionable students who are there on the voucher program. While it ideally should give bright students trapped in a crappy district the power to seek out better schools, in reality, she said that those A's they got in public school now translate into D's once in the private setting. That particular district was riddled with corruption scandals that included a heavy-handed principal that used his influence to hire friends who were incompetent and lied about their credentials during interviews. They tore down the completely ramshackle building and built a fancy new one, which now has empty classrooms that they cannot fill. The local police department also has an office within the building, if that tells you anything.

Why should we be happy to shell out hard-earned tax dollars to a district that is underperforming? That has had state funds put on hold because they aren't churning out students that meet their expectations? Districts that are obsessed with raising those all-important test scores, at any cost? If all they care about is the scores, they're not caring whether or not the kids really know the information - all it does is teach you how to be a good test-taker. If you're not, then it's a poor reflection of what you really know, and how you can apply that knowledge.

I also think of the public school teachers I know who post multiple updates about how they hate their jobs, are getting out of teaching, because the students don't care, don't do any work, the administration gives them a pass and doesn't punish them, the parents are uninvolved and couldn't be bothered. It's endless. One person I actually had to unfriend because that's all she did, in every post. Is this the new "social order?"

One thing I've noticed that is rampant in the educational subculture is the use of big words, stock phrases and jargon that basically says absolutely nothing. We can speak this way all day long, to convince people we care, that we "get it," to make ourselves look puffed up and educated. When really, it's quite the contrary. Book smarts and fancy language are impressive, but can only go so far. I saw a great interview with old-school economist Thomas Sowell, who was public-schooled in Harlem, dropped out of high school and went on to become a veritable genius in his field, graduating magna cum laude from Harvard. He said that people are always coming up to him and bemoaning his experience in the inner-city public schools, but he doesn't know what they're talking about - he said he received a good education, and those in the neighborhood around him did, too. What happened? He now thinks there are none of those channels out of poverty and the very system in place to help is actually keeping these students from succeeding.

I don't like to use the phrase 'stupid people,' perhaps just "under smart." Not as smart as they could be, maybe because they're expecting and allowing the public school to fully educate their children? Trusting them to do a good job and pick up where the parent left off? What if the parent never started to begin with? I'm sure it's a combination of things - parents that don't care or can't care, students who don't care or fall between the cracks, teachers who don't have the time and mental fortitude to work on every single kid who comes from a household where education doesn't mean squat. And the more people who don't become their "child's first teacher," who don't give a rip, the more the district - and the state - decides to step in for "the social order" and the common good and start making decisions on the child's behalf. That includes in cases where the parents most definitely educate their kids and have a high stake in their learning. What gives the district and the state the right to undermine and override the parents' authority in their child's life, especially in the presence of very aware, intelligent and involved parents? If you have a district that's primarily made up of parents who don't care, are they doing more harm than good in acting on the child's behalf, just further making them victims of the system?

I think so.

More reading:

California 12-year-olds to get HPV vaccine without parental consent

Teen gets abortion with help from her high school

Recent Posts

Friday, April 5, 2013

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Woman sues clinic for failed abortion

Posted by

The Deranged Housewife

|

| Photo credit: andreyutzu/stock.xchng |

I first read about this woman - a mom of a preschooler who attempted to have an abortion, which was unsuccessful - and ended happily (she's happy about it, just for the record) with the birth of a healthy, live infant. Thankfully, they posted a link (that most people either missed or didn't bother to read) that is a little more detailed than theirs.

The woman has a double uterus with two cervices (that's plural for cervix) - otherwise known as uterus didelphys. Apparently it's rather rare and goes undiagnosed unless the woman has problems, such as miscarriages and preterm births. From what I understand, uterine defects - especially this one - can cause repeated miscarriages, pre-term births and intrauterine growth restriction, depending on the severity of the defect. I myself have a bicornuate uterus, which is a heart-shaped variation that at the very least is why two of my children were not able to turn into the vertex position before birth.

According to the article, during the woman's first pregnancy the embryo implanted in the right uterus, producing a healthy, preterm infant delivered by cesarean. Unfortunately, the second pregnancy implanted in the left portion, and doctors felt that it could jeopardize the life of the mother if she remained pregnant.

I don't necessarily fault her for following the advice of her doctor. Nothing in this article made her sound cruel, heartless, or any of the other vile comments that some people made. She followed the advice of her physician, something many pregnant women do every day. Is the doctor always right? Depending on who you ask, that might be subject to debate.

I've read some literature from at least one OB who said that oftentimes women are given a grave diagnosis and decide to abort based on that opinion alone. Some, he reported, sought him for a second opinion and were surprised that it might not be as terribly serious as they once thought (and some definitely seek second and even third opinions only to be told the same devastating news). Really, though, when you think about it: childbirth advocates and many others often realize that many obstetricians are taught that pregnancy is an illness, a pathology. What else can you expect?

If indeed her doctor's advice was premature, or he was unnecessarily trying to scare her, this again can point the finger at doctors who are quick to suggest abortion for anomalies that are not as life-threatening as once thought. If anything, his suggestion that her uterus would be "too weak" may have been misguided or bad advice, but it all depends on the degree of deformity. If her doctor's advice really wasn't that sound, then he failed her. How many times have you heard someone say, "Just trust your doctor!" How about when he's telling you "You're stupid for attempting a VBAC, it's so dangerous,""I can't believe you're planning a home birth - are you trying to kill your baby?"

How can we fault her for just taking her doctor's advice, something every pregnant woman is encouraged to do?

So to get to the details: this woman sought an abortion from a clinic and they supposedly announced her free and clear after the procedure, only for her to find out she was still pregnant. I'm sorry, but I don't see how they can even begin to deny her claim: if you go in for an abortion and something is allegedly done to you, if you remain pregnant it's clear that they didn't do their job, correct? How can they deny no wrongdoing or negligence?

This woman then spent the rest of her pregnancy wondering what would happen: would her baby be born prematurely? Would her water break at 18 weeks and the baby die anyway, compounded by the failed efforts of the abortion clinic? I can't imagine her fear - then wondering, once the baby was born, if there would be lasting complications. And lastly, wondering, if they didn't perform an abortion, what the hell *did* they do to me?!

The point remains: they were negligent. They screwed up. Whatever the case, they said they were doing something - for a fee - and they didn't do it. What if something terrible had happened? If she had had an ectopic pregnancy and they handled it this way, there's probably little doubt that she'd be dead by now. If they didn't get sued or at least called out by her, who else are they going to mess up with?

Monday, April 1, 2013

Birth as a "Marathon"

Posted by

The Deranged Housewife

|

| Photo credit: An Empowered Birth FaceBook fan page. |

If you were a marathon runner, would you try to run the Boston Marathon after only training for a week? A day? Probably not.

Preparing for birth can be like running a marathon - although to some women, "preparing" means different things to different people. It seems that few realize the mental and physical preparation that should go into preparing for birth.

When I look back on what I knew (or, rather, didn't know) before having my children, it honestly kind of scares me. I distinctly remember my first due date approaching, the baby was breech, and I was excited to meet my child. The doctor told me that if I showed up in labor (a very real concern of mine) they "wouldn't let me go too long" before sectioning me. That was about the sum total of his counsel when it came to the risks and benefits of surgical birth. I scurried (or waddled, probably) to my car in the parking lot, anxious about the impending arrival of my new bundle of joy.

I'm fairly certain that had I really known the risks of cesarean birth, I would have rightly been scared out of my wits. I'm also sure that the reason I wasn't worried about that aspect at all was because my doctor didn't mention jack crap about it. Any of it!

This is one inherent problem in obstetrics today, it seems: a sometimes complete lack of adequate, informed consent. How can we prepare ourselves for that birth marathon when we don't know what to prepare for? There has to be more to it than breathing through some contractions, grimacing through the pain while they place an epidural, and pushing out a baby. I have heard so many women, on the eve of their inductions, say in a panicked voice, "I'm being induced tomorrow and I have no idea what to expect!" Really??

When I think back on my experiences and how they've played out over three pregnancies, there is one central idea that pops out at me: essentially, you have to start planning future pregnancies before the first one is even finished.

It sounds ridiculous, and can be virtually impossible for many women, but that's about what it all boils down to.

Before your first pregnancy is even over, ideally you should ask yourself:

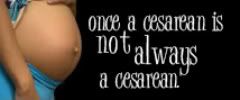

• What are the risks and benefits of cesarean? How will it effect any future pregnancies and births? (This is key!) Depending on how good or bad that experience turns out, it can not only influence how you give birth to future children, but can negatively impact your ideas on how future births may play out (which may or may not even be realized) - and some may decide to scrap their plans for a larger family and opt never to become pregnant again!

• What is my doctor's cesarean rate? More importantly, what is his/her induction rate? (Studies have shown that in first-time mothers, induction can dramatically increase the risk of cesarean section.)

• How can I avoid an induction or cesarean?

• How can I prepare myself for one if one or both become necessary? And how does my doctor define "necessary?"

Another thing that stands out to me throughout my experiences and in hearing others talk about theirs, is the idea that everything our doctors do to us and for us while pregnant and laboring is always for our benefit, and therefore always necessary. This is where you cross into a gray area, I think: some inductions and cesareans are unavoidable and quite necessary, while others are sketchy. It can be quite a conundrum.

• What if I need to be induced for having a 'big baby?' What *is* a "big" baby? I think you'll find a wide range of answers.

• What if my fluid level is low? How can I increase fluid levels? Is it really always cause for alarm?

• If I need to have a cesarean, can I request one that is more "mother-friendly?" This may entail delayed cord clamping, immediate skin-to-skin contact and immediate breastfeeding. If your doctor refuses to do this, ask why - challenge the answers if they seem hesitant or cannot give you any compelling reasons why you couldn't do this (barring an emergency or "crash" section, obviously).

Another unfortunate problem is the "bait and switch," where doctors appear to be supportive of your concerns and ideas but then mysteriously change their minds at the end of your pregnancy. This especially happens with VBACs, where a care giver seems to support the mother's wishes and then poof! Two weeks before your due date they're pressuring you to schedule a cesarean. It sounds paranoid and terrible, but all I can say is, be prepared. If your doctor is threatening you this way, know your rights, know the risks and stand up for yourself the best way you can. Hire a doula, if possible.

Something else I've noticed in talking with pregnant women and in the general population at large is that if it didn't happen to them, then it probably doesn't happen. *eyeroll* Birth trauma is an especially touchy subject for many to discuss, because so many people have come to accept these practices without question, not knowing any other way. One set of health care practitioners will be bold enough to assume that just because no doctor they've ever worked with does inductions without just cause, surely they all operate like that - while another group can vouch that many are truly "cut happy" and have a reputation for rushing through things. This tends to silence women who stand up to the bullying tactics of some care providers, marginalizing their experiences and making others think they're "conspiracy theorists" because they dare to care or push for something better for pregnant women.

If I could do it all over again, ideally I would've been more prepared with that first baby - asking more questions, demanding answers, and informing myself more. My suggestions to you are:

• First ask yourself what kind of birth you want. If you want an epidural and all that jazz, fine, have one! But be adequately informed of their benefits as well as potential risks and side effects. You have to have more of a knowledge of them than "they're safe, get one!" because that is garbage. If you're on the fence, research your options and know that there's more out there than just that. Keep an open mind about those options and how you can cope without them, including water birth, massage, walking, standing in the shower, etc. But certainly don't feel like a failure because you "caved" and asked for the epidural.

• Take a good childbirth class. This can be subject to personal opinion, honestly. To me, a "good" childbirth class entails informing you adequately about a number of options while not making you feel demonized for choosing an alternative. For instance, if you know you want a natural birth but your teacher is making you feel like an idiot for choosing one (especially issuing the ubiquitious phrase "You won't get a medal for doing it without drugs!") then perhaps that class isn't "good." Likewise, no childbirth educator should make you feel like crap because you want an epidural, nor should they gloss over the risks of them or make them sound like the Devil's poison, either.

• Read. There is a lot of material out there, (some really good and some really, really bad) and good material will back itself up with sources. However, I suggest getting your information from a lot of sources, not just one (that includes your doctor). Again, it all depends on what you want in a birth, but some sites will sway in one particular direction or another. An even mix is key: anyone that makes you feel bad for going off your diet occasionally or like everything in pregnancy is to be feared and avoided might be over-the-top. And likewise, someone that acts like there is only one way of doing things, ever! might not be an unbiased, objective source of information, either.

• Avoid people who cannot or will not give you encouragement. This is especially important if you are attempting something that most people consider unusual, risky or not "mainstream" (eyeroll) like home birth, VBAC or really, a completely unmedicated childbirth. More people than not are going to gasp, their mouths dragging the ground, and look at you like you have spontaneously grown four heads. While some people are just uninformed but well-meaning, it's probably best to steer clear of people who can't support you in your efforts and do nothing but tear you down (that includes care providers, too!).

• Realize that when it comes to labor pain, it's all subjective. If you haven't gone through it before, it's normal to be scared about it - but you never know how you are going to handle it. When people relate their horror stories to you, you have to realize that that's their interpretation of it, not necessarily how it's going to work out for you. There are so many ways you can manage and cope with it without having to immediately ask for drugs - although there should be no shame in that, either. Just realize one thing: that some hospitals make it intentionally difficult to use these coping strategies effectively, such as "not allowing" you to get into a different laboring/pushing position, insisting on continuous fetal monitoring (that can confine you to bed), among other things. Ask about a tub. Ask to move around. Don't be afraid to just ask and focus on your labor, not pleasing the staff or trying to be "nice" just for them.

• In the end, realize that sometimes the things you desire least may be unavoidable. Being emotionally prepared for this, while not dwelling too much on the negatives and "what ifs," as well as being involved in the process and made to feel like you are an active participant, rather than just a helpless bystander, can help tremendously when it comes to accepting those outcomes. When it comes to being empowered and informed, it may not prevent every intervention, but it sure can't hurt.